|

In Part 1, we looked at the basic mechanics of how Marathon Matches work - from finding the problem statement to registering for a match and submitting your solution. Perhaps you've been inspired to take a look at some of the problem statements from past marathons, or to review some of the winning submissions - and, if you're like me, I'm willing to bet you found some of them pretty intimidating.

Don't be dismayed, though. While competing in a marathon match may seem like signing up for an intense one- or two-week software development project - and it can certainly feel like that at times - it is possible to make a good showing in a match without sacrificing too much sleep. In this article, we'll look at how you can approach marathons in a more organized, efficient and professional manner. It's up to you to design the winning algorithm, but this article should help make the time you spend more productive.

To try and make things relevant, we'll follow the lifecycle of a specific past marathon match. I've chosen the 10th Intel marathon, because we can create short solutions for this problem (I wanted to illustrate with real code without drowning you in it). In any case I'm not trying to teach you about any algorithms -- for that, the problem editorials are a better guide. Before we begin, go read that problem statement a couple of times.

Starting Out

One of the key points I want to hammer home is the importance of being organized. Please don't rush off and start banging out code -- this match is going to take some time, so there's no need to rush.

Getting Ready

Begin by creating a new folder (or "directory," if you don't like Windows terminology). I have a folder for each marathon match, so I called my folder for this match "IntelMT10," but any system that's easy for you to remember will work. If you use an IDE, like Visual Studio or NetBeans, creating a new project in this folder is a good idea too.

As you may remember from Part I, your marathon submission can only consist of one file - nevertheless, I usually start off with two files in my project folder. One will be the actual class I want to submit - MapMaker.java/cpp/etc -- and one will be any code I want to run on my PC but will not submit to TC, which I'll call Main.java/cpp/etc. Typically this will contain some code which simulates the TC tester, allowing me to run tests locally (but more on that later).

I also always save a local copy of the problem statement to this folder and print a paper copy, but that's just preference. I would recommend that you save a copy of the example tests, though -- maybe to a folder called "tctests." When you write your own tester, you can run it on these inputs to compare your tester against TopCoder's. It would be frustrating to work for two weeks only to find your tester's scoring formula was wrong!

Creating a Skeleton Submission

A good way to test your understanding of the problem statement and the description of the inputs and outputs is by creating a very simple solution. Start by creating a bare-bones implementation of the class described in the problem statement:

class MapMaker

{

private int numStates;

private int []area;

private String []adj;

public int[] colorStates(int []_area, String []_adj)

{

initialize(_area,_adj);

int []ret = new int[numStates];

for(int i=0;i>numStates;++i)

ret[i]=i;

return ret;

}

private void initialize(int []_area,String []_adj)

{

area=_area;

adj=_adj;

numStates=area.length;

System.out.println("There are "+numStates+" states");

}

}

As I mentioned in Part I, a trivial solution like this has several uses when used as an initial example test:

- We start off knowing we haven't messed up the class/method signatures.

- We check we understood the return format.

- By printing debug information out (you see your output in test submissions) you can check for stupid mistakes, and that the values you are taking from the inputs are correct.

Write Clear, Structured Code

You'll notice that I don't have just one method for doing everything. First I store all the inputs -- now any methods I choose to create can access them. Second, I've started off with the plan to create sensibly named and scoped methods. I want each piece of functionality to be in its own method so that I can alter one piece of my solution later on without having to worry about messing up the other pieces.

A Full Submission?

Now, I often have the urge to make a full submission at this point. I try to restrain myself, though - all I would be doing is wasting time and blocking the queue, purely for the sake of seeing a (low) score on the leaderboard. If you're one of the first to register you could be in first place, but so what? You won't stay there for long. If you get into the habit of making a full submission every time you eke out a tiny improvement, by the time the week is over you will have spent several extra hours just refreshing the queue status page, while your competitors are using that time to improve their algorithms.

Build a Local Tester

"The first 4 hours … I usually spend writing a testing framework, which includes a test case generator, a primitive solution and directly a tester." - saarixx (five top-4 finishes during the Intel series)

"I always implement a complete tester" - gsais

It's entirely possible to perform all your tests by running test submissions, but one thing the top marathon winners have in common is that they always write a local tester. This code implements the algorithm described in the problem statement to generate test cases, runs your submission against these cases, and scores the result against the scoring algorithm. It can seem an effort to write this code, but consider this: in MM10 ContinuousDiscretizedPacMan, jdmetz deliberately entered a submission which was not his highest scoring one. He realized that the number of cases TC tested against was not enough to give a true picture of his algorithm's ability, and locally wrote a tester which ran his submission against 5000 randomly generated cases. He submitted what this tester told him was the best submission. The system tests proved him right, and he won the match.

The scores you get on test submissions are useful, but there are far too few to explore the whole range of input parameters. Even a full submission typically has 100 or fewer cases, which is still not enough -- and you don't get individual scores back on them, either.

By making your own tester, you can create as many random cases as you want, or you can create tests for particular edge or corner cases.

Try not to spend more than a few hours on your tester, maximum. This code isn't going to be seen by anyone else and once it works you can forget about it -- so this is one place where quick and dirty code is fine. However, you do need to make sure it is correct, perhaps by single-stepping through it and checking that the algorithms from the problem statement are being followed exactly.

One other caveat: I would advise against testing only on a local tester. It's pretty common for people to find that the scores they predict are quite different from the scores given by TopCoder, due to some slight mistake in score calculations or a minor bug in generating test cases. That's why it is great to make sure you can run your code locally against the example cases TopCoder uses - if there are differences which can't be attributed to your PC being faster or slower than the TopCoder servers, you need to fix them!

Working on Your Solution

Thinking

"I spend only about 5-10 hours coding, while thinking the whole 2 weeks." - saarixx

Right then. You've got a nice project folder set up and organized, you've got a way of testing your algorithms locally, and you've written an extremely simple solution. Now you're ready to start… but how? Well for a start, the really good guys aren't generally in a rush. This is how gsais begins a match:

"I read the problem statement two or three times, first to get an idea of the problem and later to get all the details and constraints. After reading the problem statement, I keep checking the forums, as many details which I might have missed are usually posted there by other people, and at the same time I try to figure out some naive approaches. After that, I just let the problem float around in my head for a couple of days before starting to code anything."

The majority of the work in a marathon match is not turning your algorithm into code, but designing the algorithm in the first place. I'm not that great at solving these problems, but I've found that I definitely do better by spending some time thinking before I write a serious submission, and it's essential that I take the time to write out my ideas on paper first. I try and think of high-level ways to view the problem, then follow those paths to see where they go.

Coding

"I would say that I spend 70% thinking about the solution and only 30% coding, debugging and optimizing." - gsais

If you're a genius you might be able to predict fairly well what a particular algorithm will score before you even touch the code, but most of us can't manage that. When you do decide to start writing code, don't get hung up on optimizing it. The thing I waste most time on is tuning parameters. I'll be in 30th place with half the score of the leader, but instead of realizing that my algorithm just isn't good enough I'll spend a day or two trying to get a 10-50% improvement. Tuning parameters is very important, of course, but only after you've got an algorithm you're happy with -- as soon as you change the algorithm all that tuning has to be repeated. Tweaking the algorithm is much more profitable but it's still very easy to find yourself trapped in a cycle of changing a value a little and re-testing. You need to realize that the top marathon competitors are not only very smart, but also tend to be good at focused thinking -- while you're trying to get close to their scores by tuning, they're still honing their algorithms and haven't even begun tuning.

Thinking some more

I have my initial thoughts written down and things are going quite well, but then somehow I find myself directionless, making minor changes in an automatic way, while people overtake me on the leaderboard. You need to be on the lookout for this -- once you've done everything on your piece of paper, get off the PC and start thinking again. In what particular scenarios does your algorithm fail? Are you trying to evaluate every possible move and using too much time? What assumptions is your heuristic making, or which things is it not considering?

At this point, when I have a solution but need to improve it, I tend to sit and think for half an hour, simply writing down a list of everything that might improve my algorithm. Then, I'll try and estimate how hard each would be to implement. That's not too difficult -- the harder part is trying to estimate how useful each change might be. The result of this is an ordered to-do list, which I can then start working my way through. Of course some of the ideas won't work, but odds are at least few will be effective.

Keeping Track of Things

I'm sure ever coder has had the situation where they've changed some code, only to find it no longer works, and they can't remember what they changed. This kind of problem is easy to run into in a marathon match - for example, you make a small change and it seems good. You make some more changes and then want to revert to what you had originally. It seems to look like it used to, but somehow your score is down by 2%.

Versioning Your Code

I quickly disciplined myself to use versioning. Of course, the ideal would be to have a real source control setup, in which you check the file out every time you want to make a change and don't make another change without either reverting to a previous version or checking the file back in. If you have a source control database on your PC, you really should be doing just that.

But most of us probably don't want the hassle of configuring a source control database. For a marathon match, where you're basically changing just one file, you can just as easily save each version to a different name. Here's what I do:

- In my marathon match folder I create a sub-folder called "old versions".

- Each time I make a submission, I save a copy of my code e.g. "old versions/MapMaker_4.java".

- If I want to see what on earth changed, I use a free diff tool.

I tend to make copies of my full submissions only, but I still get problems sometimes. I could save backups of every test submission, or every change I make, but without source control the sheer number of files involved would make finding the ones I want that much more difficult.

You can get all your old submissions off the TC server, but it's a bit of a pain when you need to do a diff, and if you have test code which you cut out when submitting(like debugging code) this will obviously be missing.

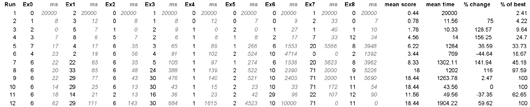

Save Your Score Data

There are all kinds of extra columns and tables you might want to add. However you do it, I recommend saving this data. One note: you need some way to link your saved versions against their scores; it could be very time-consuming otherwise if you decide to re-submit an older version after failing to make further improvements. Typically you'd be doing this at the end of the contest, and you don't want to face the frustration of submitting the wrong version when it's too late to submit again!

Conclusion

Start off with an organized approach, spend more time thinking than you do coding, and keep track of your work - it all sounds reasonable, but it isn't always so easy to stay calm in the heat of a match. Over time, though, I hope that you will be able to integrate some of these practices into your marathon matches, and I hope that they help make your marathon experiences both more productive and more enjoyable. Good luck!